This essay, taken with permission from the book Let's Talk About Truth (Ave Maria Press, 2020), explores how to form good judgments in a "post-truth" society by distinguishing between objective facts and subjective judgments. Using Chris Argyris' "Ladder of Inference" model, it explains how personal experiences, culture, and background shape how we select and interpret data to form opinions. The author, Ann Garrido, emphasizes three key principles for sound moral judgment: remaining grounded in reality, informing one's conscience through education and reflection, and considering impacts on others, especially the vulnerable. For navigating disagreements, the essay recommends assuming good intent, listening deeply, sharing reflectively from one's own perspective, and seeking divine guidance while acknowledging that resolution isn't always possible.

Truth is a way of forming good judgments

In an earlier essay, I introduced “living” truth in relation to the classical definition of the term: always striving to have one’s mind be in alignment with reality. When we talk about truth in this way, we are asking questions related to the existence and nature of things. We are trying to find out what is and what is not. Nothing in the universe half exists. Either you were born in the state of Indiana, or you were not. Either the earth is 4.6 billion years old, or it is not. In common parlance, there is no way to be “a little bit pregnant.” Additional information might change our understanding of how something is true. For instance, Aristotle, Newton, and Einstein each hypothesized how gravity works differently, but none of them doubted that gravity is. “Doing truth,” at this most foundational level, is about making sure that we have the best grasp possible of what would widely be referred to as “the facts.”

The human mind, however, does more than simply collect facts—which often can be verified or rejected or refined on the basis of observation and logic. The mind also collates facts, organizing them in such a way that they make sense to us as a whole. The mind uses what it has gleaned from the world to arrive at statements such as:

It’s true that gambling is wrong.

The fact of the matter is no one should drive drunk.

That judge is racist—you can’t deny it.

As a matter of fact, we had plenty of kids to merit keeping the parish school open.

Even though these are also truth claims, these beliefs are of a different nature than belief in gravity or quarks. It is hard to tell the difference in the midst of a conversation, because the language is so similar. But these statements are not so much about whether or how something exists but whether something is good or bad. They are about whether someone should or shouldn’t. Whether this is better than that. Even when we label them as facts, these are not facts; they are judgments—or we might also say opinions, conclusions, convictions—that people hold as true.

To say that something is an opinion is not to say that it’s not true, but rather that it is true (or not) in a different way. May I suggest that you read that last sentence twice? It is an important one and not easy to grasp. We are now talking about truth as it pertains to meaning making and decision making, and we don’t want to mix apples and oranges. We often do, including in the act of preaching. The conflation of fact and judgment is a good part of what makes talking about truth in a post-truth society feel so hopeless and stuck. But, we take a step in a helpful direction when we make a critical distinction: While reality itself is objective, the person who tries to make sense of it and to figure out what to do in the middle of it is always a “subject,” a unique individual who is shaped by the particularities of life and circumstance including personal experiences, a family of origin, the geography of a home, a culture with its native tongue, a specific set of desires and feelings, differing degrees of formal education, etc. And, each of the above factors into the way that a person makes meaning of and judges the world, making truth claims of this nature more difficult to adjudicate than truth claims related to facts. (And Galileo thought he had it tough!)

What all goes into the making of an opinion?

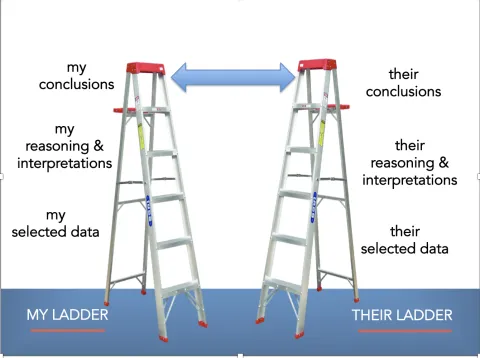

I acknowledge up front, that this is not a question currently being asked by most congregations, but as preachers, we want to explore it anyway because without considering how opinions are formed, the other questions related to judgment will prove challenging to address. Indeed, if we could stir an interest in this question among hearers, I suspect half of the conversations they currently find so frustrating could easily be resolved. A most helpful framework for beginning to explore the question is the work of Harvard Business school professor Chris Argyris who in the 1970’s constructed a model called the Ladder of Inference” to describe the process that the human mind goes through in order to arrive at the opinions it holds about the world.[i]

At the base of Argyris’ model exists all of the data—or facts—that are available to me. This lowest level of the model parallels what we talked about in chapter 1 as “objective reality.” Recall that what-is-available-to-me is not the totality of all the data that exists on this matter. Others may have access to data that I do not, and all of us together will likely still not know all that could be known on any matter.

But, even of the data that is available to me, Argyris’ model points out that my mind only pays attention to some of it. Why? Because the data I could be paying attention to is immense and overwhelming! And life has taught me that only some of it is necessary to pay attention to. How did I learn that lesson? Life experiences, especially while growing up.

Early on, for instance, I learned it was more important to listen to the voice of the teacher in the front of the room than to count the number of tiles on the classroom floor, or the fly buzzing around in the air, or Amy and Melissa passing notes behind me. Paying attention to one set of data points earned me an A in class. Paying attention to another set of data points could land me in the principal’s office. So, over the course a lifetime, I was repeatedly socialized by family, friends, educational systems, work cultures, religious communities, etc… to unconsciously privilege the voice of the authority in the front of the room more than the other things going on in the space. Most of the time I am unaware that I am doing so. In my own mind, I am just paying attention to the facts that matter. I am simply noticing what is important.

Once my brain has selected data to pay attention to, it begins to assign meaning and interpretation to the data, again based on what the particularities of my own life experience and cultural context have previously taught me. So if, for example, I go outside to the church parking lot after a spring rainstorm, I could be paying attention to the puddles on the ground or I could be paying attention to the sky. In essence, experience may have taught me to privilege looking in one direction over the other… especially if I’ve soaked my feet previously in surprise puddles. But let’s say that my eyes are on the sky and I see a rainbow. Based again on my own background, I might think to myself, “What an amazing meteorological phenomenon caused by the refraction of light on water droplets!” or I might think to myself, “Genesis. God set his bow in the sky.” Because I’ve been coloring pictures of Noah and the ark since I was four, and I did just come from church after all, let’s say the rainbow reminds me of the biblical account.

When I step in my front door, I share my conclusion with my brother: “You know what? Everything is going to be okay in the world. We should have hope.” And he, sodden and wet, is utterly puzzled from whence this grand proclamation suddenly emerged.

The Ladder of Inference helps to explain not only how the mind arrives at conclusions, but why different minds arrive at different conclusions. It helps to explain why a group of people—all sincerely open to reality and endowed with the gift of reason—could still end up holding very different ‘truths.’ In many disagreements, it turns out that we do agree on the facts. What we disagree about is which facts matter, which facts we should be paying attention to and which ones are less relevant, what the facts mean, and how they should be interpreted.

Although Argyris’ model was not designed to capture Catholic intuitions about how the brain arrives at judgments, it aligns nicely. Thomas Aquinas similarly observed:

“Even though the sense always apprehends a thing as it is unless there is an impediment in the organ or in the medium, the imagination usually apprehends a thing as it is not.” [ii] Aquinas affirms that, unless we have some sort of physical or mental deficiency, it is not our ability to grasp the world through our senses that is the source of our differences of perception. The challenge lies at the level of our imagination—the way that we form the facts into a picture in our minds.

Even though each of us has an abundance of experience and history and culture and family story, etc… shaping our “imagination,” the lower rungs of our Ladders often go unexplored in our own personal reflection, in our conversations with each other, and in our preaching. In a fast-paced world where we are under pressure to make choices quickly, we tend to exchange words with each other only from the top rungs of our respective Ladders: Let me tell you what’s true. This results in a frustrating back and forth argument, as you try to persuade me to share your conclusion and I try to persuade you to share mine. It is as if we each want the other to make a leap 10 feet above the ground from the top of their Ladder to the top of ours, when experience suggests that the only way a wise person would shift from the top of one Ladder to another would be by descending the rungs of their own Ladder one by one and then ascending the rungs of the other one by one. [iii]

Aren’t We Entitled to Our Own Opinions?

Our lives as preachers would be a lot easier if everyone in our congregations began to explore the question of truth in judgments from a reflective stance, “Why do I hold the opinions I hold? How did I form my judgments?” I suspect most instead approach from a confrontational stance: “Aren’t I entitled to hold my own opinion?” It’s a question that comes with a lot of embedded assumptions we’ll need to handle with great care in the pulpit.

The Ladder of Inference helps to explain why—even though we all live on the same planet—we still arrive at such different notions regarding how to live on it. What the Ladder of Inference doesn’t help explain is what to do about the fact that we hold such different truths or beliefs. Some might say there is nothing that needs to be done about it. Each person is free to stand upon his or her own Ladder. Each person is free to hold and act upon his or her own beliefs. Ultimately the Christian tradition affirms that statement (as we will discuss momentarily when we get to conscience) but not before adding a whole lot of nuance into the mix. Christianity also reminds us that as human beings, whether we want to be or not, we are part of a wider community. The tradition sees this as a good thing: God made us to be in relationship—with God and others. It is only by living in community that we learn and grow and become who God dreams us to be. Yet it also means that our beliefs—and the actions that result from those beliefs—are going to impact God and others, whether we want them to or not. No man is an island.

Sometimes our differences in judgment don’t matter much. I hold that my college alma mater is the best place ever. My son picked another university. My brother wanted the baby’s room to be orange. My sister-in-law green. Some are so minor that we might even label them differences in preference. Negotiating such differences often involves compromise, flipping a coin, splitting the difference, or each of us doing our own thing. The world is no worse for the wear. We might say that these judgments are of an “amoral” nature. They are not immoral. Rather, they are “differences that don’t make much of a difference” in our ability to be in relationship.

There are many cases, however, where our differences in judgment do matter and each person doing their own thing is not inconsequential. Given how intertwined we are, even things that seem like highly personal choices—how I vote, how I drive, how much I drink—have implications for others’ lives. I may not believe in immunizing my child and claim a right to make that choice for my own family, but my child will cross paths in the world with your child in school and on the playground. If your child is immune-compromised, my beliefs and the choices I make based upon those beliefs could endanger the life of your child. I may not believe humans contribute to climate change, but you and I both breathe the same air and depend upon the same water supply. Your health is also at stake.

When our truths have consequences for relationships they become “moral” in nature. And so, even though it is very difficult to assess the truth of a judgment, we need some way of being able to do so in order to live on this planet with one another without erupting into violence—our age-old means of “resolving” consequential differences for which the world is worse for the wear. While everyone has opinions, some opinions are more true—or worthy—than others.

Note the shift in our working definition of truth here. We are now striving for something different than described in my earlier essay. Previously our objective was to know reality. Practicing truth meant having a mind aligned with reality. In this chapter, our objective is to figure out what would be best. Practicing truth in this sense means having a mind aligned with the greatest good. And, the quest for the good—like the quest for reality—comes with a well-worn map, but still no step-by-step, foolproof guide.

The Catholic tradition has multiple ways of naming the greatest good that we are aiming for. Jesus called it “the Kingdom of God.” The Catholic social tradition often refers to it as “the common good.” Ultimately, we might simply name it “God.” As preachers speaking to congregations who may be unfamiliar with the rich theological nuances behind each of those terms, perhaps the easiest door thru which to enter a conversation about the Christian notion of “the good” is John 10:10The thief only comes to steal, kill, and destroy. I came that they may have life, and may have it abundantly. in which Jesus says, “I have come that they may have life and have it abundantly.” The greatest good is a flourishing of life. And so, when assessing the truth of a belief of a moral nature, what we are in the broadest sense asking is, “Does holding this belief lead toward a greater flourishing of life or not?”

That’s tricky, isn’t it? Thomas Aquinas himself admitted as much. Aquinas noted that there were certain principles that all people of goodwill around the earth were inclined toward naturally as leading toward greater life, but he acknowledged that persons of goodwill might still come to different conclusions in concrete situations that involved the application of those principles—an exercise he referred to as “practical reason.”[iv]

It turns out that the worthiness of an opinion can’t be measured with a ruler or verified by observations through a telescope. As preachers, we will need to lift up a different set of commitments to help hearers “live truth” with regard to the formation of judgments that impact others. There are three concepts from the tradition that I suggest we regularly integrate into our preaching in order to help congregants assess and strengthen their own process of working up the Ladder of Inference to arrive at “true” conclusions:

Remain Grounded in Reality

As described in detail in my previous essay, the Catholic tradition holds that there is such a thing as reality. Any judgment that we arrive at that doesn’t have its footing in reality is bound to be a faulty judgment. If we do our diocesan planning based on recent census demographical information, and the census data is inaccurate, it doesn’t matter how careful our interpretation of the data is; the opinion we arrive at will be less “true” than it could be. If we are trying to decide which particular cancer treatment to pursue, but our doctor has accessed erroneous research data, it doesn’t matter which part of that data our doctor bases a recommendation on; the recommendation is less “true” than we want it to be. When working up the Ladder of Inference, before selecting the data we think worth paying attention to and trying to make sense of that data, we need to make sure we are working with real data. This is what makes “fake news” so dangerous in our own time. We are forming judgments grounded in erroneous or absent data. Because reality is immense, it is always possible to learn additional facts, but by definition it is not possible to have “alternative facts.”

Inform Your Conscience

In place of the American maxim, “Everyone is entitled to her opinion,” the Catholic tradition upholds, “Everyone must follow her conscience.” At first, these two statements sound similar, but a closer look reveals them to be quite different.

Conscience, like reason, is a gift from God, a unique human capacity. While reason especially helps us align our mind with reality, conscience helps us align our mind with the good. It helps us distinguish in the core of our being between right and wrong. It helps us to figure out what would be the greatest good in a particular situation and how to act on that good. The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World—one of the most significant documents of the Second Vatican Council—says of conscience: “Its voice, ever calling him to love and to do what is good and to avoid evil, tells him inwardly at the right moment: do this, shun that.” [v]

In Catholicism, conscience—similar to the American concept of opinion—is sacrosanct. It is to be respected and no one should be asked to violate her conscience. In that sense, everyone is “entitled” to act on her conscience. But unlike the common notion of opinion, conscience is understood to be fallible. The same document states “conscience goes astray through ignorance which it is unable to avoid,” but also for “the man who takes little trouble to find out what is true and good” and for the one whose “conscience is by degrees almost blinded through the habit of committing sin.”[vi] Hence, every person is obligated to make certain that his conscience is well formed. In addition to listening to one’s own deep intuitions around what is right and good in any situation, a person must educate himself regarding the facts and must be open to the wisdom of family, friends, colleagues, and experts in the field. If Christian, the person must consult scripture and the teachings of the church. The individual freedom each has to arrive at a belief and act upon it comes with the responsibility of due diligence.

One of the things the Ladder of Inference makes clear is how much our individual processes of arriving at judgments are influenced by factors of which we are barely aware in the moment—our families of origin, our culture, our personality traits, etc… The church’s teaching about conscience asks us to wake up to what is in the lower rungs of our Ladder and become more intentional about what filters we want data from the outside world to pass through as our judgments are formed. As human beings we are influenced and shaped by these environments. But we also possess a capacity that no other creature seems to possess: the ability to influence and shape our environments. We are both the products of our cultures and the creators of our cultures.[vii] We can work to become increasingly aware of what lies in the middle rungs of our Ladder. We can ask if those influences are the ones that we want to be shaping our data selection and interpretation. By what we read, what news stations we watch, who we chose to befriend, and how we decide to spend our time, we can change the way our mind filters and makes sense of information.

The church’s conviction is that intentionally forming our conscience, like intentionally developing our gift of reason, will lead us to greater unity with one another while still honoring our individuality. The Pastoral Constitution asserts: “Through loyalty to conscience Christians are joined to other men in the search for truth and for the right solution to so many moral problems which arise both in the life of individuals and from social relationships.”[viii]

Consider the Voice of Those Impacted

Subsidiarity may seem like an odd concept to be introducing in a chapter on pursuing truth in our judgments. As a principle in Catholic social teaching, it was given voice in the 1931 encyclical Quadregesimo anno to encourage governments to give as much authority as possible to local communities, never taking on functions at the national level that could be handled just as well, or even better, at the local level.[ix] The interest behind this principle, however, is that those who are most impacted by a decision should be the ones who have the most say in how it is made.

We see this interest at the very center of Jesus’ ministry. Over and over again Jesus showed his concern for those negatively impacted by the way his own society was structured—widows, children, lepers, etc. He spent a great deal of time talking with these people and making sure their concerns were heard and addressed. In his preaching, he encouraged the Pharisees to become aware of the way that their rigid proclamations and judgments were impacting others, repeatedly asking them to take on a new perspective in the way they were reading situations. In the end of time, Jesus taught, we all will be judged by whether or not we attended to the cries of “the least” in our own choices.

But what about others who don’t agree with us?

So let’s say that we are doing our best to inform our conscience and arrive at sound judgments rooted in reality, conscious of the impact our beliefs may have on others. What do we do about the fact that others hold different beliefs than we do, some of which are “differences that make a difference” for us? It’s a question on the hearts and minds of many listeners.

The church has struggled mightily with this question over the centuries. Historically, the church has tested a wide range of options in response to others who do not share what the church holds as true, including everything from praying for the person to arresting them to excommunicating them. In our current pluralistic environment, some of these options no longer make sense (and most of us, I think, would add the phrase “thank goodness”). Furthermore, such grand solutions as excommunication have never been available to individual Christians in disagreement over such issues as whose turn it is to take out the garbage. There are times that I would like to have all the power of the law behind me when it comes to solving once and for all issues related to living in common with others, but I don’t, and so I need other, more practical strategies.

Many preachers see communications coaching as outside their job description. Yet, if we want people to be able to “live” truth in their daily lives, that charge inevitably includes being able to talk through “differences that make a difference.” Helping people to overcome differences was certainly a key concern of Jesus’ in his proclamation of the Kingdom of God and the scriptures open many doors to reflect on what we’ve learned as best practices in this regard. What follows are four practices that we can regularly encourage in our preaching to equip hearers for handling conversations in which another holds a different “truth.” These are practices we can also model in the construction of our own preaching, especially when we talk about those who disagree with what the church holds as true.

Assume Charitable and Reasonable Intent

When we have been careful in the formation of our own opinion and another still thinks differently than we do, our natural impulse is to assume the other is either invincibly ignorant or in the throes of sin. Both of those are possibilities. Ignorance and sin have played a role in human judgment from the earliest pages of Genesis. But the gospel admonition “do not judge”[x] suggests that in times of difference, we should first assume basic intelligence and good intent on the part of the other. In our own head, we may be saying, “The reason why X won’t see things my way is that she is flat-out crazy.” But in her own head, X is probably not thinking, “The reason I won’t change my mind on this matter is because I’m flat-out crazy.” In X’s head, her opinions somehow do make sense and our first goal is to try to understand why.

Sin and ignorance are possibilities, but it is also possible that X has different data than we do; has selected different data to pay attention to than we have; or is interpreting that selected data differently. Again, as Thomas Aquinas notes, sometimes the difference of perception between us may simply be rooted in the natural messiness of “practical reason.”

Chances are there is a bit of sin and ignorance intertwined with natural differences in “practical reasoning” for X, but chances are that it is the case for us as well. Even as intelligent people with good intentions, we still can be unaware of ways in which the filters we use to select and interpret data may be infected with traces of “isms” (racism, sexism, ageism, elitism, etc.) Knowing how much we would like our own possible blind spots to be handled charitably by others, we can lean into conversations assuming the other is a person of intelligence and good will not consciously intending to do harm.[xi] In our effort to model this practice, we should be careful not to malign any group from the pulpit including in the use of labels to describe the group that no one in that group would use to describe themselves or their motivations (e.g. Abortionists, The Gay Agenda, Relativists, Racists, Elites).

Listen at the Lower Rungs of the Ladder

When we want to practice Christian love toward someone who holds convictions different than our own, the most powerful action we can take is to listen. As noted earlier, conversations around differences of opinion tend to start at the top of the Ladder of Inference. We want to move the conversation to the lower rungs of the Ladder by asking questions that will help us to understand what lies beneath the other’s conclusions: Tell me about what you are seeing that you think I might be missing. What do you think I should be paying more attention to? This sounds like it is really important to you. Why? What are you feeling about this experience? What does this experience mean to you? What kinds of experiences have you had that shape your thinking on this? What are you concerned would happen if we went in another direction? What would be lost if we did ___ instead?[xii]

In the end, we still may not agree with their opinion, but we’ll understand better why this opinion makes sense for them. We can note that if we had the same experiences, if we were working with the same data, if we were living under the same conditions, we might share similar conclusions. And, sometimes that will be enough. As Benedictine sister Joan Chittister says, “What most people need is a good listening-to.”[xiii] We arrive at a degree of peace, acknowledging that we look at the issue differently but it doesn’t need to continue impacting our relationship.

In the pulpit, it is tough to model what good listening looks like. Usually there is one person doing all the talking! Dialogical homilies have their own challenges. But one can easily integrate stories that include snippets of dialogue where the kinds of questions listed are explored. We can paint a picture of what good listening looks like since, sadly, many hearers have not had the experience in their own lives of receiving a “good listening-to.” We can also give evidence in the pulpit of having listened deeply to other perspectives. When mentioning a person or group that sees things differently than you or the church, describe the other’s position in such a way that if a member of the “opposing” party were present in the congregation on that day, the person would be able to nod and say, “Yes, that is what I believe. You might not agree with me, but you heard what I was saying and represented my concern fairly.”

Share from the Lower Rungs of Our Ladders

Often we’ll find that—even though we now understand the other’s perspective better—we are still not okay with “agreeing to disagree” on this issue. We also have a voice and it wants to speak. It wants to explain itself; to share why it holds what it holds. It wants to talk about how it is impacted by the other’s beliefs. And, for the sake of integrity, it is important that our own perspective is shared, even if the other won’t change their mind (or even listen!)

Just as we come to deeper understanding of the other by exploring the lower rungs of their Ladder, the other has a better chance of understanding us if we speak from the lower rungs of our Ladder, and if we do so from a stance of curiosity. Every Ladder is complicated, including our own. And, how our opinions form is a bit of a puzzle, even to ourselves. If we can demonstrate that we are curious before our own Ladder, it invites the other to ask more questions of us, and possibly even spurs the other to look at their Ladder more carefully. We do this by verbalizing aloud what we wonder about when considering our own Ladders: I realize that _____ might be at stake for me. I’d like to think that I’m not motivated by ______, but sometimes I wonder if I am. When I hear you say that, an alarm bell goes off inside my head. I’m not entirely sure why. I suspect a piece of it is_____. My experience of ______ has shaped my thinking on this. There are probably other experiences that I need to spend more time thinking about.

Pope Francis has said that a healthy dose of doubt is important in the pursuit of truth. In parallel fashion, expressing doubt is an important part of exploring what we hold as true. Instead of only sharing the data we have that supports our opinion, we can share also the data we’ve gleaned that doesn’t. We can acknowledge to the other what we think the weak spots in our own arguments might be and what we consider to be strongest points in their argument. Doing so can quell the urge in the other to defend their view because it alerts them we are already aware of the contrasting data and thinking about it. It implicitly invites the other to be transparent about their own doubts, bringing the conversation to a new place where we might discover overlapping concerns.

Preachers, again, can model this kind of reflection in the pulpit. For example, when preaching on a moral teaching that some hearers might find tough to swallow, after describing charitably the opposing point of view, rather than just share the church’s conclusion, the preacher can describe what was the original data the church was working with. What is the church worried about or concerned might be lost? What has been the impact of the teaching that the church might continue to reflect on?

In the words of Pope Francis, “To dialogue means to believe that the ‘other’ has something worthwhile to say, and to entertain his or her point of view and perspective. Engaging in dialogue does not mean renouncing our own ideas and traditions, but the claim that they alone are valid or absolute.”[xiv]

Asking for Divine Help

In any conversation worth its salt we come away having learned something new. Dare I say, most of time what we learn will deepen a conviction we already hold? But unless we are already perfectly “true” in all our judgments, it would seem that at least some of the time, what we learn should be changing our minds.

It’s tough to change one’s mind because we get attached to what we hold as true. As numerous studies document, we humans suffer from “confirmation bias.” Once we have reached a particular conclusion, we will pre-sort all future data coming into our Ladder based on what it is we already hold—drawing upon agreeable data to reinforce our perspective and dismissing other data as irrelevant.[xv]

As part of a faith tradition that preaches the importance of ongoing “conversion,” confirmation bias presents a real danger for Christians. We want to be firm in holding on to our convictions, faithful to the wisdom that has been passed on to us. At the same time, we don’t want to shut ourselves off from learning something new or lose the ability to change our minds. And so we constantly struggle to find the right balance between conviction and openness.

If anyone figures out exactly what that right balance looks like, alert the pope. Meanwhile, as we try to live that tension rightly, we can practice bringing the struggle to prayer: God, I don’t know how to talk with X any more. God, help me know whether you want me to be more open here or whether you want me stand firm or whether you want me to live with the ambiguity. God help the two of us to break through this impasse. As noted earlier, God cares a great deal about our ability to communicate with one another, because God wants us to be able to enjoy communion with one another—and those two are deeply linked. These are the kinds of prayers that God delights in answering.

Preachers can certainly lift up the role of prayer in working through differences and even incorporate examples of prayer into the preaching itself.

And when nothing works?

It’s the question so many of our congregants ask in deep pain. Unfortunately, there are no magic words, no magic techniques for breaking through tough conversations around the truth of each other’s beliefs. Occasionally, after giving it our all, even after prayer, we will still find ourselves in a state of impasse. It can be helpful at that point for each party to clarify: Is there anything that would change your mind on this matter? Is there data that you would find persuasive? What would you have to see in order to change your opinion? Naming what would persuade one to change one’s mind can give the conversation a potential path forward.

But sometimes not. Sometimes we’ll discover that no evidence to the contrary would be sufficient to change another’s mind, in which case there may be no purpose to continuing to talk about it. We can discuss whether and how to remain in relationship in a later esay. But for now, as preachers we should be honest about the human experience of limitation. As much as we might want to bring about a harmony in which all beliefs are held in common, this is ultimately beyond our control. Our planet’s future—the Kingdom of God of which Jesus speaks—ultimately rests in the hands of God. Even Jesus in his own preaching ministry was unable to change peoples’ minds. Dealing with this realization is part of what it means to “live” truth as well.

Summary

Living in a post-truth society raises challenging questions for contemporary Christians: Not only “What is truth?” but “How do I put together all I’ve learned to form ‘truths’ (i.e. judgments, opinions, conclusions that I hold as true)?” and “How do I talk with those who’ve constructed their data to arrive at different truths?”

Part of announcing the “Good News” in a contemporary congregation involves lifting up what we’ve learned as a faith community over the past 2000 years about how we arrive at truths and also how we can assess and continually “improve” our truths—i.e. how we can always be trying to align them with the greatest good. And part of announcing the “Good News” means highlighting and modeling best practices related to respectful dialogue around truths even in the midst of disagreement. In our preaching, we want to:

- affirm that—while reality exists and we can know it—our judgments about how best to make sense of it and live in it are shaped in ways that we don’t entirely understand by the various cultures in which we function (family, society, educational systems, faith traditions, etc.);

- affirm that when our judgments impact others, they become moral in nature and must be formed responsibly, which can only happen if we have an ongoing commitment to be grounded in facts; develop our conscience; and consider the impact of our judgments on others, especially the poor and vulnerable;

- equip hearers with concrete practices for talking with others about differing beliefs, specifically: assuming charitable and reasonable intent; deep listening; speaking reflectively about one’s own data and interpretations; and praying for divine assistance;

- acknowledge that we do not ultimately control the outcome of tough conversations around conflicting beliefs and sometimes have to “shake the dust.”

Although in the end, we may not arrive in a place of agreement, Thomas Aquinas reminds us, “We must love them both, those whose opinions we share and those whose opinions we reject. For both have labored in the search for truth and both have helped us in the finding of it.”[xvi] Whenever we preach about ‘truths’ we want to do so in such a way that it becomes clear: the place of our most profound disagreement with one another is simultaneously the place of opportunity to practice Christian love in a most particular way.

[i] What I present here is in simplified form. The original Ladder of Inference designed by Chris Argyris has seven rungs. See C. Argyris, Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning (NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 1990). Argyris’ thought was popularized by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (NY: Doubleday, 1990)

[ii] Thomas Aquinas, Quaestiones disputatae de veritate, article XI (available at: http://dhspriory.org/thomas/english/QDdeVer1.htm#11). Likewise, the 12th century Christian thinker Anselm of Canterbury asserts, “It seems to me that truth or falsity is not in the sense but in opinion.” See: Anselm of Canterbury, qtd by Thomas Aquinas in Quaestiones disputatae de veritate, article XI

[iii] “As nobody can judge a case unless he hears the reasons on both sides, so he who has to listen to philosophy will be in a better position to pass judgment if he listens to all the arguments on both sides.” Thomas Aquinas, Metaphysics III lec 3

[iv] Thomas Aquinas, Summa II-I, q. 94, a.4 – Thomas gives here the example of theft – widely regarded as wrong. And so when something it is it stolen it should be returned to the rightful owner, yet “Now this is true for the majority of cases: but it may happen in a particular case that it would be injurious, and therefore unreasonable, to restore goods held in trust; for instance, if they are claimed for the purpose of fighting against one's country. And this principle will be found to fail the more, according as we descend further into detail, e.g. if one were to say that goods held in trust should be restored with such and such a guarantee, or in such and such a way; because the greater the number of conditions added, the greater the number of ways in which the principle may fail, so that it be not right to restore or not to restore.” The more particular we move in terms of context, the greater the need for prudence to figure out what would be the greatest good in this circumstance.

[v] Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et spes) Vatican Council II, Flannery edition. (NY: Costello, 1992) #16

[vi] Ibid., 16.

[vii] Michael Paul Gallagher, SJ analyzes this theme as found especially in the writing and preaching of Pope John Paul II in Clashing Symbols: An Introduction to Faith and Culture (NY: Paulist Press, 2003): 49-62.

[viii] Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et spes) Vatican Council II, Flannery edition. (NY: Costello, 1992) #16

[ix] Pius XI, Quadragesimo anno (May 15, 1931) #79: "Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do. For every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them."

[x] Matthew 7:1"Don't judge, so that you won't be judged.

[xi] Thomas Aquinas. Summa II-II, q. 70 a. 3 ad. 2: “Good is to be presumed of everyone unless the contrary appears, provided this does not threaten injury to another.”

[xii] For preachers wanting to develop their own skills in this area, I highly recommend the book Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen (Penguin, 2010).

[xiii] Joan Chittister, correspondence qtd in Joan Chittister, The Play, by Teri Bays. It was in Act 3. for more information, see http://www.joanchittister.org/new/joan-chittister-play

[xiv] Pope Francis, World Communications Day 2014

[xv] As an example of one of the seminal studies on this topic, see Peter C. Wason, “On the Failure to Eliminate Hypotheses in a Conceptual Task,” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12, no. 3 (1960): 129-140.

[xvi] Thomas Aquinas, Metaphysics XII, lec 9 (#2566)

- Log in to post comments